My mother’s grandmother, Grace Stewart Guilfoil, came to Michigan in 1919 with her husband Albert and five of their eight children, to live and work on the farm between Douglas and Fennville on the river road, where we now live. I’ve written before about genealogical research, and the pleasure you get when it all comes together to tell a story. I’ll describe my work on the Stewarts to show how the small pieces of information you gather about your family come together to make a story.

About Grace’s family – I knew they lived in Pueblo, Colorado and had come from Pennsylvania, from the area where the Johnstown flood had taken place in 1876. Family legend said her father was a civic official of some sort in Pueblo, that he had been in the Civil War, and that his name was Spencer. His wife’s name was Mary, and her maiden name was said to be McIntyre or McInnerney. Grace had met Albert because she had gone to school with his sister Estelle in the East, though both were Coloradans. I knew Grace had a sister Annie, who had helped raise my mom's cousin June Smith Connor; a sister Mary, who later married Fernando Leal and lived in California; and another sister Ede. Grace had died in 1940, before any of my siblings or cousins, the grandchildren of her daughter Dorothy Guilfoil Audett, were born, so we could learn nothing firsthand about her family from her.

Her husband Albert’s father was also in the Civil War, and opposed to the splashiness of his military career, Grace’s father’s career was not a legend in the family. John H. Guilfoil was something of a self-promoter and a little bit of a rogue. He had fought at Shiloh. He was active in the Grand Army of the Republic in Colorado. When he died the obituary in his hometown paper said “Boy Drummer of Civil War Dies In West” and his drum was one of the ornaments of Albert’s and Grace’s farmhouse.

So when I began work on the Stewarts I started with the cemetery in which most of them were laid to rest, Roselawn Cemetery in Pueblo. This cemetery has very good search tools and interesting historical comments online. I learned that the Stewarts were in a Catholic section of the cemetery – no big surprise there. Buried in that lot were:

Anne M. Stewart, buried January 1, 1934, aged 63.

William Spencer Stewart, buried October 21, 1932, aged 52.

Mary E. Stewart, buried August 27, 1923, aged 76.

Gertrude Stewart, buried February 3, 1903, aged 19.

Alice, Genevieve, and James S. Stewart, buried June 10, 1892, ages shown as zero.

It made perfect sense that none of the married daughters, Grace, Mary, or Ede (Edith), who had married a man named Edward J. Lodge, were buried with their parents. The library in Pueblo offered to send obituaries from the Pueblo Chieftain, the local newspaper, and I got one for William Spencer Stewart, from the October 28, 1932 edition. It was a model of brevity: “William S. Stewart, at U.S. Marine hospital, Ellis island, New York. Brother of Anne M. of Pueblo, Mrs. A.C. Guilfoil of Fennville, Mich., Mrs. Mary Leal of San Francisco, and Mrs. E.J. Lodge of Wellington, Kas. Member of Pueblo council, Knights of Columbus. Announcements later.” Of course, there were no later announcements, and William Spencer Stewart had already been buried by his sister, Annie, a week before the obituary ran. An obituary for Mary E. Stewart from the same paper in 1926 turned out to be an unrelated person.

Family legend had it that Mary E. Stewart, Grace’s mother, had died while visiting Grace in Michigan, but obviously, if that had happened, her body was returned to Pueblo for burial in the family plot. As to who Alice, Genevieve, and Gertrude were – I couldn’t be sure—and I didn’t know whether James S. was the “Spencer” of family lore, and thus, Grace’s father. The State of Colorado had a website listing “Veterans Grave Registrations”, and both James S. Stewart and William Spencer Stewart were shown there. That suggested that James S. was indeed the Civil War veteran I was looking for, but what kind of military service his son William Spencer had had was unknown to me.

About then I looked through my grandmother, Dorothy Guilfoil Audett’s, photograph album. This is in an album labeled “Places and Faces”, and mostly recorded family pictures from her courtship and early married life in Seattle in the 1910s. There were two photographs that were of interest in my research about the Stewarts. One was labeled, and the other was not. The labeled one was of Mary E. Stewart, her daughter Grace, her granddaughter Ruth Guilfoil Smith, and her great-granddaughter June Smith Connor. June had been born in 1913 and was a baby in this picture.

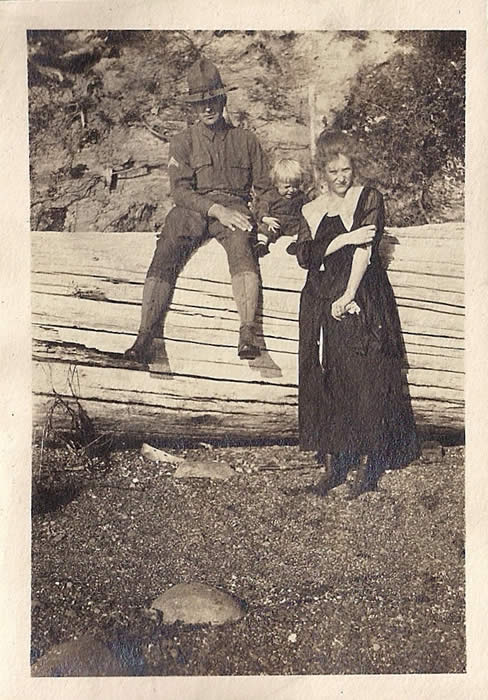

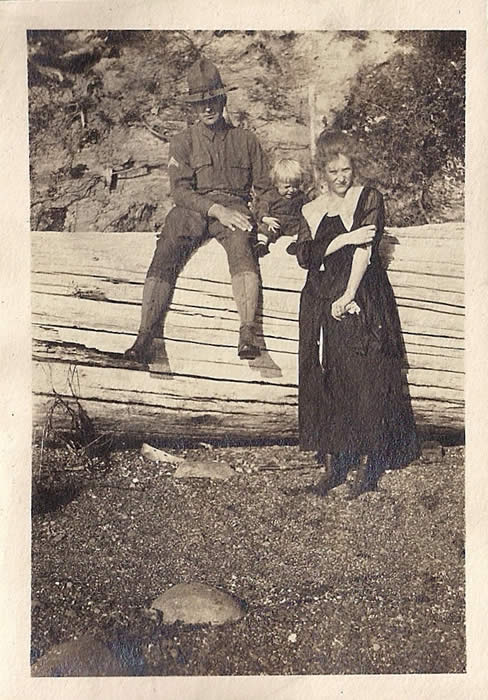

The unlabeled one showed my grandmother, Dorothy Guilfoil Audett, and her daughter, my mother, Dorothy Audett Hanson, as a small child. They were photographed with a serviceman, in a uniform of the first World War, sitting on a large fallen tree, a typical photographic setting of the Seattle snapshots in my grandmother’s album. There was another photo in the same place with this serviceman and a young woman.

Thinking about who this serviceman could have been, I concluded that it could only have been Dorothy Guilfoil Audett’s uncle, William Spencer Stewart. None of her brothers were old enough to serve in the first World War, nor were there other uncles of the right age. It could indeed have been a friend. She was already married, though, and why would she and her daughter be pictured with a friend from before her marriage?

I spent some time looking for the Stewarts on the census databases that are now generally available on the internet. In 1920 Albert and Grace were on the farm, with their children Albert, Stella, Richard and Grace and their granddaughter June Smith. Grace’s sister Anne M. Stewart was a lodger with a family in Pueblo, and her sister Edith was also in Pueblo with her husband Edward J. Lodge, their children, Edward’s brother, and his son. I wasn’t able to locate either Mary E. Stewart, or William Spencer Stewart, on the 1920 census.

In 1910, Mary E. Stewart was living in Pueblo with her grown children Anne, William, and Mary. William is a machinist in a steel mill. In 1900, Mary E. Stewart was living in Pueblo with the same children, none grown except Annie and William, who, it says is a machinist’s helper, and also with Gertrude and Edith. Because the 1900 census collected such information, I learned the year and month of birth for everyone – for Mary it was August, 1847, and for William Spencer it was February, 1880. So if the serviceman in the picture with my grandmother and mother was William Spencer – and since my mother, who was born in 1917 was one or two, no older – William Spencer would have been about 38 years old. This man could have been that age.

As one tends to do when you have as few datapoints as the usual family genealogist has, I jumped to a conclusion. It occurred to me that since William Spencer Stewart had died in the U.S. Marine hospital on Ellis Island, that perhaps if I could determine if the uniform and insignia of the serviceman in the World War I photograph were Marine Corps, that I would be able to determine William Spencer Stewart’s military service, and thus, be able to retrieve a record of that service. I sought the help of a friend who had been in the Marine Corps, and, as such people often do, he enlisted the help of other Marines. It was their conclusion that there were issues with the cover and the insignia, and that the serviceman was not a Marine. We all looked closely at the photograph and at historical paintings of Marine actions from about that time, and eventually my friend found a curator at the Marine Corps Museum who supported the view of the several experts – the serviceman was a soldier, not a Marine. Afterwards, doing research on what the U.S. Marine Hospital at Ellis Island was, I learned that it had started as a hospital for merchant sailors, but had quickly had to take on the responsibility of evaluating and processing the endless stream of immigrants to the United States from the 1890s through to 1924, when new immigration laws cut off the flow. By 1932, it probably had reverted to serving its original clientele, the merchant seamen coming into the port of New York.

I still don't have any information about William Spencer Stewart's military service, or even if he had any at all.

With regard to James S. Stewart, there was also information on the census databases that helped me establish that the man buried at Roselawn Cemetery in Pueblo was definitely Grace’s father. In 1880 he was in St. Clair Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, with his wife Mary, daughters Anna, Grace, Alice, Genevieve, and his infant son William S. He is a clerk in a store, and the family has a servant. In 1870 James and Mary, without children, are in Armagh village, Blairsville post office, Indiana County, Pennsylvania, which is in the same area as their 1880 location. James is a clerk in a store.

I called up Roselawn cemetery in Pueblo and asked them, why were Alice, Genevieve and James S. shown on their database with ages of zero? I thought I knew the answer already, from reading about the history of the cemetery on their website, and I was right: the three relatives’ graves had been moved to the new Roselawn cemetery from an earlier one when the cemetery was established in 1892. The ages shown on the Roselawn cemetery data and the ages from the earlier census data all fit. Alice and Genevieve were daughters of James S. and Mary E. Stewart who died in their youth, and James S. Stewart was my great-great-grandfather, Grace’s father, born in 1844. The Colorado State Archive’s Veterans Grave Registry showed his birthdate as October 1, 1844.

There is an admirable website, maintained by the National Park Service, which is called the Civil War Soldiers’ and Sailors’ System. On this website you can look up names and find out in what regiments or other units Civil War servicemen were. There were 96 James Stewarts in Pennsylvania regiments. Sifting through them is something of a daunting task, when you want to find which James Stewart was your great-great-grandfather. I looked through the list and checked off regiments that were raised in the general area of Pennsylvania where I knew James S. Stewart had lived after the war. One that seemed a good candidate was the 100th Regiment, Pennsylvania Infantry. Another website, www.pa-roots.com, has voluminous histories and data about those regiments. The 100th Regiment was known as the “Roundhead Regiment”, raised mostly from Scots-Irish settlers in western Pennsylvania. Company M was raised in Westmoreland County. There was a James Stewart in it. He enlisted September 5, 1861 and was mustered out with the regiment July 24, 1865. This guy had a hell of a war: Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Vicksburg, the Wilderness, and then, the Mine at Petersburg, where he was taken prisoner. The National Archives offers the compiled service records of Civil War veterans. I ordered one for this man, thinking he might be my great-grandfather. When it arrived, I discovered he was not. It happens. He was a 32-year old miner born in Ireland – my great-great-grandfather was a 17-year old born in Pennsylvania, from parents also born in Pennsylvania. The Company M, 100th Infantry Regiment James Stewart, however, had beautiful penmanship, as I learned from his letter requesting furlough to take care of his aged parents. So, another dead-end in research.

A subsequent request to the City of New York for his death certificate yielded William Spencer Stewart's actual date of death – October 16, 1932. He was not a resident of the city – so maybe was a merchant seaman. His occupation is listed as plumber. His mother Mary’s name was listed as McGwer. The National Archives sent a copy of William Spencer Stewart’s September 12, 1917 draft card. Date of birth, February 27, 1880. Occupation machinist. Living with his mother Mary at 3406 38 S.W., Seattle, Washington. It occurred to me to write to the Colorado State Archives. They knew that James S. Stewart and William Spencer Stewart were veterans. It therefore followed that they would know what their units and dates of service might have been. The State Archives wrote back. They had the information, and would send it once I sent them a check. When it came, James S. Stewart was listed, on a card someone filled out in February, 1941, as having been a corporal in Company H, 12th Pennsylvania Regular Engineers. He was born in Indiana County, Pennsylvania on October 1, 1844 and died in Pueblo May 19, 1890.

There was no 12th Pennsylvania Engineers regiment but James S. Stewart turned out to be in Company H of the 12th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry, raised in Indiana County. My cousin, Steve Audett, checking the same websites I mentioned up above, learned that James S. Stewart enlisted July 24, 1861, was wounded at the battle of Antietam September 17, 1862, and was discharged from the service May 16, 1863. The 12th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry went on to Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness. I’m glad James didn’t have to go through all that after Antietam. There were more casualties on the day he was wounded than on any other day in American military history.

The William Spencer Stewart card, put together also in February, 1941, had a mistake that was rather amusing. His birthdate was shown as February 27, 1880, which I already knew from his draft card. But his military service was with the 2nd Colorado Cavalry Regiment during the Civil War, and he enlisted January 5, 1863 and was discharged Sept. 23, 1865. The researcher back in 1941 had confounded my great-grand-uncle William with another William Stewart. It happens.

James S. Stewart’s service became clear when compiled military service record arrived from the National Archives. I also ordered his pension records, and they told me more about his origins and his life after the war. They were an absolute gold mine. James Spencer Stewart collected a pension, and after he died his wife Mary E. McAteer Stewart tried to qualify for a widow’s pension. She had six small children, and no doubt could have used the money. Because of a technicality she didn’t get a pension until 1902. Much of the pension file – UPS dropped off a two-pound envelope – consisted of her applications and supporting documentation for that pension.

James S. Stewart joined the 12th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry on July 24, 1861. He was sixteen. A year later, in September, 1862 at Antietam he was wounded, a gunshot wound to the left hand. He was in the hospital in Reading, Pennsylvania, returned to duty in December, 1862, then was discharged, due to the wound in March, 1863. He went back home to Armagh, Pennsylvania, applied, and was granted a pension. The doctor wrote the government James was “wounded by a ball in left hand although the wound is now healed the hand is much disabled". Three fingers were said to be useless, the whole hand much weakened, and the hand was smaller than the right.

Nevertheless, he reenlisted on February 29, 1864 for three years in Company D U.S. Engineer’s battalion, and was promoted to corporal in 1866. After he got out he married Mary E. McAteer in Johnstown or Altoona, Pennsylvania on July 17, 1867. They had nine children: Annie (1870), Grace (1873), Alice (1875), Genevieve (1877), William (1880), Gertrude (1882), Edith (1884), Richard (1886), and Mary (1888). They moved out to Pueblo, Colorado by 1882. The whole family appeared on the special 1885 Colorado census. James was county clerk.

Mary lived on with her children in Pueblo on Evans Street. Alice died at some unknown date. Genevieve died in 1891, Richard in 1897, and Gertrude in 1903. It sounds like Annie’s job at the post office kept the family afloat for a good while. By 1917 Mary was in Seattle with William.

Mary did indeed die at the farm near Fennville, Michigan where her daughter Grace lived. My cousin John Sheridan found her death certificate and sent it to me. She died on August 23, 1923. He also sent me a letter that Mary’s daughter Mary had written to his grandmother, Grace Guilfoil Oakley, about her family, which confirmed many of the things I had found out in my research.

|